Medieval History

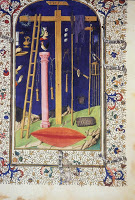

Prester John is only visualized when he is racialized. I've only seen images of him once he is Ethiopian, later in his career within the Western imaginary. His early days in India, chronicled in the letter from him that emerges in the 1160s, do not seem to have produced portraiture. And so what's an art historian to do when she really really wants to teach the letter because a) it's awesome (that bed of sapphire!), b) Uebel's book about Prester John, Ecstatic Transformation, is phenomenal, and c) we need to tackle this issue of non-representation as much as that of representation? The short answer is that instead of teaching images of Prester John, I presented images of the perception that Prester John produces: lists, fragments, discontinuities. This move was much inspired by Uebel who treats the fragmentary and the discontinuous in his analysis of the insistent listing (of animals, monstrous races, gems, spices, palace furnishing, landscapes, and more) of the letter. The more I read Uebel, the more I began to think of the "thrill of the fragment" so prevalent in medieval art. The Arma Christi above are a simple (but thrilling) enough example: this is one of two pages that present the weapons used at Christ's crucifixion in a completely discontinuous framework that thoroughly fragments that narrative of the Crucifixion. The sponge filled with vinegar that Christ was given to drink stands (lies?) next to the spear that pierces his side; the three nails that will enter his hands and feet are next to the chalice that will catch his blood.

There are some extreme examples. Yes, that's Malchus's ear suspended there, and a soldier's spit in mid-air, and that is indeed the wound of Christ now huge stretched out below (on the ground?). I asked the students to articulate the experience, the process of looking at this image. At first, it was what it was not: it was not narrative, it was not connected, it was not linear. Then they offered other terms: spaceless, timeless, suspended... in short (or so Uebel helped us see), utopic. And this is where it got really exciting for me, being able to connect the fragment to utopia through the framework of loss. For what are these images of Arma Christi but a fragmentation of the Crucifixion, the loss of Christ's body and presence? One that must be compensated for in every Eucharistic performance, one that must be (yes) re-membered in every liturgy.

And so the letter of Prester John is born from this dynamic of fragment, loss, and utopia, one that, for Uebel, defines medieval Christianity well beyond the dynamic as it applies to Christ. My students leaped: "Is the loss of the Garden of Eden then responsible for colonialism?" (For Prester John, a Christian ruler in India descended from the Three Magi, was always already a colonialist - a product of the colonial imagination, conquering wondrous lands shimmering through fragments, promising a return to the West to enrich and protect it). Colonialism is too righteous and complex a phenomenon to be explained that succinctly, but one does think of the repercussions of a fragment, loss, utopia dynamic. Especially when we can see it, and imagine its performance. We ended class with the Stavelot altar, a portable altar (for when you need to take your fragment, loss, utopia dynamic on the road). Portable altars have always fascinated me: they carry (reduce, condense) much - namely, the entire liturgical and spatial framework of religious architecture. You're supposed to be able to consecrate a host on them, bring forth the body of Christ, recover the loss through the fragment in this utopia. As such, they are mystical (almost magical) objects themselves, containing relics, as the Stavelot altar does, beneath central crystals.

Or presenting an abstract surface, as the Adelhaus altar does, its central space of consecration filled with the formlessness of porphyry - a resonant echo of Prester John's bed of sapphire.

- Thing-power In The Classroom: Stones, Ladders, Spit, Onions, Phalluses And Roses

We've had a new student join our Ecology of Medieval Art class, and it was to him that I turned first in asking for a description of the image on the screen (the same one that you see here). "An arrangement of minerals, stones, and quartz,"...

- Beauty, Fantasy, Difference

Bosch, Epiphany, 1500, the PradoThere are more papers, more events, more bureaucracies, more of everything that needs to be swept away for just a few minutes. Balthasar has been on my mind since Tuesday, when we entered the third theoretical framework...

- Fragments

Arma Christ. Musée Jacquemart-André, ParisIn the 10 minutes before I need to start gathering the kids from their play dates, I think that I can put into words why writing has eluded me of late. I've wanted to everyday, but the balance of navel gazing...

- Lenten Array 2011

The ancient western custom of covering altars and images with Lenten array and Lenten veils has been covered on this blog a number of times. If you want to know more about the custom and its purpose look at the article here and...

- Five Wounds Of Christ

Angel holding the arma christi, a shield charged with the five wounds. It is unusual to see this subject in colour, usually it is rendered in yellow stain. This image from Lawrence Lew's wonderful photostream, is taken from a panel of fifteenth...

Medieval History

Fragmentation, Loss, Utopia

|

| Arma Christi, c.1300 |

|

| Arma Christi, 15th c. |

|

| Stavelot Altar, c. 1175 |

|

| Adelhaus Altar, c. 875 |

- Thing-power In The Classroom: Stones, Ladders, Spit, Onions, Phalluses And Roses

We've had a new student join our Ecology of Medieval Art class, and it was to him that I turned first in asking for a description of the image on the screen (the same one that you see here). "An arrangement of minerals, stones, and quartz,"...

- Beauty, Fantasy, Difference

Bosch, Epiphany, 1500, the PradoThere are more papers, more events, more bureaucracies, more of everything that needs to be swept away for just a few minutes. Balthasar has been on my mind since Tuesday, when we entered the third theoretical framework...

- Fragments

Arma Christ. Musée Jacquemart-André, ParisIn the 10 minutes before I need to start gathering the kids from their play dates, I think that I can put into words why writing has eluded me of late. I've wanted to everyday, but the balance of navel gazing...

- Lenten Array 2011

The ancient western custom of covering altars and images with Lenten array and Lenten veils has been covered on this blog a number of times. If you want to know more about the custom and its purpose look at the article here and...

- Five Wounds Of Christ

Angel holding the arma christi, a shield charged with the five wounds. It is unusual to see this subject in colour, usually it is rendered in yellow stain. This image from Lawrence Lew's wonderful photostream, is taken from a panel of fifteenth...