Medieval History

We've been spending the semester in my medieval art history class thinking about "Painting and Presence." Petrus's Carthusian Monk was my avatar on Facebook, I found him at the Met - we're in deep. Though I knew (with great relish and anticipation as I contemplated teaching these lush works of art with their vital wood supports, their vibrant oil surfaces, their fervent color projections, and their intense degree of illusion) where the course was going in terms of content, I didn't really know where it was going to go conceptually. I had set up "painting" as an emerging category (the newness of oil and its visualizing possibilities, the shifts in patronage arrangements, the gathering of different audiences) and "presence" as a kind of open category (aura? power? theology? ontology?).

I don't expect the category of "presence" to be the same for every class (students' interests and my own will push and pull that different ways each time I teach this course, I hope), but this time, it was definitely ontology. The existence, the conditions of being, grappling with what it means to be so many things: painting as object, painting as vision, painting as devotion, patron, patron as image, patron as soul, and objects, so many objects that positively glowed by the time we'd realized we'd been talking and writing about them for weeks: shoes and mirrors and dogs and candles and windows and textiles (oh the textiles!) and tiny sculptures writhing on bedposts and the ends of benches and fruits and windows. What were they all doing and being? And though my writing presents them as a cascade of things, in each painting they are neatly arranged, suspended in a poised quiet.

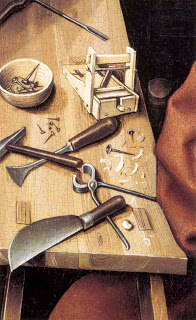

If (if!) a hammer is a hammer when it hammers, what is it (doing and being) when it is in a work of art? (An equally good question, with a fantastic answer from the painter himself, is to ask after and asparagus: go ahead, look at Manet's one asparagus and ask!)This alone makes me wish we'd read more Heidegger, more Bogost, more Morton, more Harman, more Bennett - more object oriented ontology all over the place. (It also makes me wish that Harman and Morton would take their awesome art criticism to medieval art). The question is one that art history has asked in its own within-the-frame way (and, in being our "writing in the major" course, "Painting and Presence" has a historiographic element): a hammer is not ever (ever!) just a hammer ever since Panofsky wound the connecting threads of "disguised symbolism" into Early Netherlandish Art. It is the tool that helps Joseph make the mousetrap that will catch the mouse that is the devil for whom Christ is the bait from the typology of that one Psalm. The field of art history has wrestled much with disguised symbolism and social history has done tremendous work to shift the conversation. And yet, far from social history and deep into questions of being and painting, ontology and representation, that Panofsky started asking, this detail from the Mérode Altarpiece that holds some very prized objects has everything I want to be thinking about right now: tools, representation, and a table. Friday afternoon, I denied all grading and obligations and read Sarah Ahmed's essay "Orientation Matters" in the New Materialisms anthology and she wrote of tables (from a table) with Husserl and Heidegger and Derrida, and I can't stop thinking about objects that orient ontology, objects that are the starting point (Husserl's mode of orientation) for existence. You can start (oh my goodness anywhere, but let's just say) with the hammer in the world that Campin saw, and translated into representation. That represented hammer then does work an in-the-world hammer never could: it can (if our interpretive minds respond to it this way) be a symbol, or engaged in the symbolic construction of the devil-catching mousetrap. In some ways, the bigger challenge is just letting the hammer be. But I learned with elemental eco-criticism that we seldom let even the smallest blade of grass be, we and our yearning minds.

And so I am left to think of these arrangements on tables, on wooden tables and wooden boards that become paintings. Of objects without symbolism, objects that might be "in and of themselves" objects, except they never are, being, as they are, pigments suspended in oil swirled over polished and treated wood. Except that they are objects because my mind perceives them so and is able to see great meaning in them (symbolic, radical - think Dian Wolfthal's piece from the Troubled Vision anthology about this very mirror). As Jeffrey Cohen's marvelous book on stones gathers, as I savor what Tim Morton has me thinking about in Hyperobjects, I want to think more about simultaneity and being: a stone as inert and vital; a painting as representational and real, an object as itself and salvation.

- Shoes From The Middle Ages, Early Modern Period, Topic Of Lecture In London

From the skin-tight boots sported by dandies in the early 19th century to the brothel-creepers currently making a come-back on the streets of trendy East London, footwear has long played a powerful role in the human imagination as a signifier of rank...

- Musca Pictura

A nice little slew of deadlines have successfully been met and thus an hour's play with an old friend opens up. The fly that sits (oh my goodness, where?) upon the painting, and the sill, and the frame, of Petrus Christus's Carthusian Monk from...

- Really Real

Courbet, River Landscape (private collection!)I'd forgotten my camera and kind of cursed doing so and kind of tried to love the freedom you're supposed to have when you don't have a camera. The odd result was that I was louder: more exuberant...

- Thing-power In The Classroom: Stones, Ladders, Spit, Onions, Phalluses And Roses

We've had a new student join our Ecology of Medieval Art class, and it was to him that I turned first in asking for a description of the image on the screen (the same one that you see here). "An arrangement of minerals, stones, and quartz,"...

- Israel Tomorrow

Rembrandt. Jeremiah Lamenting Jerusalem. 1630This painting does not express the mood all around here, which is one of jubilee and anticipation, but it's just too beautiful a painting to not consider for just a bit. Of all of the things that I have...

Medieval History

Objects that Orient Ontology

|

| Petrus Christus, Carthusian Monk |

|

| Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini |

I don't expect the category of "presence" to be the same for every class (students' interests and my own will push and pull that different ways each time I teach this course, I hope), but this time, it was definitely ontology. The existence, the conditions of being, grappling with what it means to be so many things: painting as object, painting as vision, painting as devotion, patron, patron as image, patron as soul, and objects, so many objects that positively glowed by the time we'd realized we'd been talking and writing about them for weeks: shoes and mirrors and dogs and candles and windows and textiles (oh the textiles!) and tiny sculptures writhing on bedposts and the ends of benches and fruits and windows. What were they all doing and being? And though my writing presents them as a cascade of things, in each painting they are neatly arranged, suspended in a poised quiet.

|

| Campin, Mérode, tools |

|

| Christus, Goldsmith, coins and a mirror and... |

- Shoes From The Middle Ages, Early Modern Period, Topic Of Lecture In London

From the skin-tight boots sported by dandies in the early 19th century to the brothel-creepers currently making a come-back on the streets of trendy East London, footwear has long played a powerful role in the human imagination as a signifier of rank...

- Musca Pictura

A nice little slew of deadlines have successfully been met and thus an hour's play with an old friend opens up. The fly that sits (oh my goodness, where?) upon the painting, and the sill, and the frame, of Petrus Christus's Carthusian Monk from...

- Really Real

Courbet, River Landscape (private collection!)I'd forgotten my camera and kind of cursed doing so and kind of tried to love the freedom you're supposed to have when you don't have a camera. The odd result was that I was louder: more exuberant...

- Thing-power In The Classroom: Stones, Ladders, Spit, Onions, Phalluses And Roses

We've had a new student join our Ecology of Medieval Art class, and it was to him that I turned first in asking for a description of the image on the screen (the same one that you see here). "An arrangement of minerals, stones, and quartz,"...

- Israel Tomorrow

Rembrandt. Jeremiah Lamenting Jerusalem. 1630This painting does not express the mood all around here, which is one of jubilee and anticipation, but it's just too beautiful a painting to not consider for just a bit. Of all of the things that I have...