Medieval History

"Becoming" (and its partner "fetching") has always fascinated me as a word signifying something beautiful, or at least pretty and pleasant. So wayward and complex is the English language (the pronunciation conundra of labels/lapels and cough/through/dough are the tip of the iceberg) that the very same word "becoming" has two different etymologies altogether. There is "becoming" as gerund: "a coming to be, a passing into a state". But there is also "becoming" as adjective derived from "comely" (as bejeweled is from jeweled). And comely (as this morning's OED romp revealed) is an Old English word, cymlic: beautifully constructed, delicately fashioned, fittingly wrought. "Becoming" then has its roots in the description of objects, finely made, but it's come to describe the beauty of persons, too. Becoming object and becoming person meet in the "Dream of the Rood," to which I've made a glad return in finishing an essay on the "hewn" (and oh my yes, that's a great etymological trajectory, too). There, the tree that becomes the wood that becomes the cross is a beautiful personified object, an object that speaks and marvels, and trembles with gladness and desire when Christ's (of course beautiful) body is placed upon it. It is trees, then, where the ontological and aesthetic cadences of "becoming" meet. Ever since being a companion to that early morning hunt, and granted, since thinking about trees a good deal over the past months, I've come to see them as shifting forms, Ents on the run, oscillations between states of being and beauty; I've come to see them as becoming. While Deleuze and Guattari may have resented their firmly planted roots and their hierarchic reach, there's room, in the ache and growth and, dare I say it, manipulations of trees by the human imagination to understand becoming trees in their state of perpetual becoming: to see them as unstable forms, opening to fear and transformation and beauty.

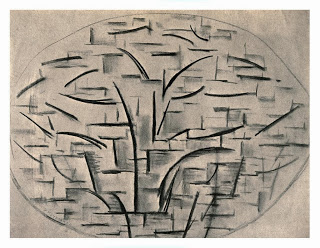

And so Piet Mondrian draws and draws an apple tree in an insistent series of black chalk on paper renditions. If you Google "Mondrian Trees" any number of fascinated bloggers will take you through the transformation from landscape art to abstract art better than I can here. It's not so much the trajectory that fascinates me (though the "visual etymology" of trees in Mondrian paintings is a lovely little piece of knowledge) as the instability. Mondrian is not progressive in his tree paintings: there is no simple trajectory from lush tree to grid. Instead, there are a series of simultaneities and oscillations between branches and bars. In trees, rather than seeing an icon of stability and seasonal return, Mondrian sees fragmentation and disintegration, a hide and seek of predictable form, and elusiveness of shape. I wonder now if he, too, didn't at some point see dawn in the forest, or the sun etching (yes, that's the word) the apple tree in his yard into lines.

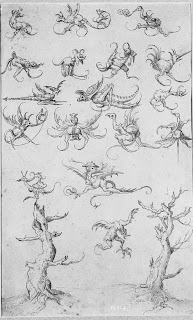

Who knows, as one must ask, what Bosch was seeing? But there's reveling in the instability of form here, as comely creatures float up from the tree's form and the artist's pencil. These finely wrought grotesques that fascinate because they are so sure and possible, and so creepy that we really hope they're not. Deep in the OED entry on "comely" is the idea of difficulty and suffering: the effort of making the thing that is finely wrought, the dark side of the delicate: its worry and failed first attempts. Here is Bosch at play, worrying (over) tree forms until by the end it's the breath of a frothy bird and the weird gas coming out of the ass of a tusked insect. Here, as with Mondrian, I might want to be comforted by the trajectory of an abstraction, by the dematerialization of rough boring bark into abstracted tendril. But, like Mondrian, Bosch stays true to form: it's trees all the way up. Limbs (and oh how wonderful is the phrase "tree limb") and branches and shoots all over the page...

... a dynamic of shifts and transformations that happens insistently. It starts (if we wanted to choose a starting point, but really, there may be no origin here) at the bottom of the page, in the fantastic confrontation between the tree on the right whose face frowns at the flying creature whose talon/root limb reaches out to land, its own right limb still an uprooted tree part. "Who are you?" "What have you become?" Iris, who has just emerged ready to delight in the thick snowfall coming down outside (and is of course bedecking the tree outside the window in its own white mantle of snow) has just made this more interesting: the "limb creature," as she calls the flying one, has just broken free from the tree on the left and seeks another companion to liberate itself, a cleaving the tree on the right, frowns upon, maybe unwilling but certainly helpless to stop the proliferation of forms.

... a dynamic of shifts and transformations that happens insistently. It starts (if we wanted to choose a starting point, but really, there may be no origin here) at the bottom of the page, in the fantastic confrontation between the tree on the right whose face frowns at the flying creature whose talon/root limb reaches out to land, its own right limb still an uprooted tree part. "Who are you?" "What have you become?" Iris, who has just emerged ready to delight in the thick snowfall coming down outside (and is of course bedecking the tree outside the window in its own white mantle of snow) has just made this more interesting: the "limb creature," as she calls the flying one, has just broken free from the tree on the left and seeks another companion to liberate itself, a cleaving the tree on the right, frowns upon, maybe unwilling but certainly helpless to stop the proliferation of forms.

- Researchers Track Climate Change In Northwest Africa Back To The Middle Ages

An international research team has figured out northwest Africa's climate history by using the information recorded in tree rings. The trees sampled contain climate data from the medieval period, including one from Morocco that dates back to the year...

- Being There

Actually, Sts. Cosmo & DamianI wonder if this is how we might have appeared to her, two still strange creatures - high up, transfixed, similarly bedecked, the one on the right making hesitating gestures, the one on the left more sure. She worked around...

- Home. Here. Home.

That old tree in that one place.I don't know where to begin. How to separate out any emotion enough to see it and write about it. It's not that there are so many (happiness, gladness, wonder, and memory really are it), it's that they're...

- Woodlands, Trees, And Timber In The Anglo-saxon World

Woodlands, Trees, and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World *14th -15th November, 2009* *The Institute of Archaeology* *University College London *Keynote speakers:* > Oliver Rackham > John Blair With a guided tour of the Museum of London stores and new Medieval...

- Obscure Latin Word Of The Week

This week's word: palmifer - fera, -ferum abounding in palm trees. How to use this word in daily life: 1. As a compliment - "My what a palmifer garden you have! I've never seen so many palms in one place." 2. As a pick-up line - "Baby, if your...

Medieval History

Becoming Trees/Trees Becoming

|

| Mondrian, Tree II, 1912 (Minn. College of Art & Design) |

|

| Mondrian, Apple Tree, 1912 (Minn. College of Art & Design) |

|

| Bosch, drawing, Cooper Union Museum |

- Researchers Track Climate Change In Northwest Africa Back To The Middle Ages

An international research team has figured out northwest Africa's climate history by using the information recorded in tree rings. The trees sampled contain climate data from the medieval period, including one from Morocco that dates back to the year...

- Being There

Actually, Sts. Cosmo & DamianI wonder if this is how we might have appeared to her, two still strange creatures - high up, transfixed, similarly bedecked, the one on the right making hesitating gestures, the one on the left more sure. She worked around...

- Home. Here. Home.

That old tree in that one place.I don't know where to begin. How to separate out any emotion enough to see it and write about it. It's not that there are so many (happiness, gladness, wonder, and memory really are it), it's that they're...

- Woodlands, Trees, And Timber In The Anglo-saxon World

Woodlands, Trees, and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World *14th -15th November, 2009* *The Institute of Archaeology* *University College London *Keynote speakers:* > Oliver Rackham > John Blair With a guided tour of the Museum of London stores and new Medieval...

- Obscure Latin Word Of The Week

This week's word: palmifer - fera, -ferum abounding in palm trees. How to use this word in daily life: 1. As a compliment - "My what a palmifer garden you have! I've never seen so many palms in one place." 2. As a pick-up line - "Baby, if your...