Medieval History

- Vasconia, Independent With Aquitaine (660-769)

The Basques were brought to heel in 635 after a gigantic Franco-Burgundian expedition. The Basque leaders vowed loyalty to Frankish king Dagobert I, but after his death the Merovingian dynasty sank in a steady decline started with the so-called rois...

- Siege Of Narbonne (752-759)

The Siege of Narbonne took place between 752 and 759 led by the Frankish king Pepin the Short against the Muslim stronghold defended by an Umayyad garrison and its Gothic and Gallo-Roman inhabitants. The siege remained as a key battlefield in the context...

- Battle Of Toulouse (721)

The Battle of Toulouse (721) was a victory of an Aquitanian Christian army led by the duke Odo of Aquitaine over an Umayyad Muslim army besieging the city of Toulouse, and led by the governor of Al-Andalus, Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani. The victory checked...

- Newport?s Medieval Ship Could Have Been Basque

The origins of the Newport Medieval Ship may have finally been solved ? with new research announced yesterday pointing to the north of Spain. Thanks to recent advances in tree-ring dating, experts have obtained the first scientific evidence that...

- Catching Up On Some Posts

The following (or in this case I suppose are preceding) are catch up posts: LAST CALL FOR PAPERS The End of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse, the Rise of the Franks, and the 'Beginning of France': A Symposium on the Occasion of the 1500th Anniversary...

Medieval History

.

The Duchy of Vasconia: Extent and Organization

The Duchy of Vasconia (or Wasconia) was initially (AD 602) a polity created by the Franks aimed at holding sway over the Basques. The first dukes appointed were of Germanic stock, but Vasconia was far away from the Frankish heartland and despite its suzerainty to the Frankish central rulers, the Duchy started to develop its own political dynamics and went through different periods until it broke up in a myriad of counties (9-10th century) that led to the formation of the Romanic Wasconia (in Latin scripts, Gasconha in Gascon), rendered in English as "Gascony" during the late Middle Ages, and its eventual political dissolution into Aquitaine in 1058.

|

| Alavese Plains in the one-time Gallia Comata Credit: Iñaki LLM |

EXTENT

At the time of the Merovingian dynasty founded by the King of the Franks Clovis, a duke was a military commander appointed to the borderlands of the kingdom where a hostile people had been subdued, e.g. Frisians, Saxons, or Basques, so he was in charge of fighting them, but also of dealing with them in political and administrative terms. Therefore, the duke, cited as dux Wasconum, e.g. Lupus II in 769, was styled as ruling over a certain people, the Vascones, and not so much over a territory, while that also came into being, with the name of Vasconia.

However, that territory is not delimited clearly, and undergoes an initial expansion up to the mid-8th century followed by a gradual shrinking and disintegration period up to 1058—annexation by Aquitaine. The Frankish king Dagobert I made in 628 arrangements for his brother Charibert II to rule over the territories between the Loire and the Pyrenees (''limes Spaniae'') 'in the general area of Vasconia', including Saintes, Perigueux, Cahors, Agenais, etc.

Furthermore, in the following years, the same king is reported to have subdued the whole Vasconia, beyond the Pyrenees too. This period, late 620s to early 670s, bears witness to Saint Amandus' failed attempt to convert the Basques to Christianity and his visit to an episcopal see across the Pyrenees, thought to be Pamplona in Frankish hands. During the same period Basque raids descending from north of the Pyrenees are attested in Visigothic records, attacking even Saragossa. It's known too that no representative of Pamplona attended the Councils of Toledo from 589 until 684.

The Ravenna Cosmographer calls "Vasconia" to the whole territory extending north up to the Loire river during the years of Basque-Aquitanian independence (660-768), so do the Continuations of the Chronicle of Fredegar, suggesting that it lies right across the Loire river. Some authors have put down this expansion of the name so far north to the Frankish negative propaganda in order to disrepute Aquitaine, inasmuch as the Basques were regarded as rustic, non-Romanized people. It seems more plausible the existence of a significant Basque component in central Aquitaine besides Gascony, rather than a single territory to the south of the Loire inhabited by Basques or under their rule. Adding to the confusion, the Basque troops were at the core of the Aquitanian army and deployed all over Vasconia and Aquitaine, even darting out of the territory, e.g. expeditions against Peppin on the siege of Narbonne in 754 and Peppin's Burgundy and Narbonne in 762.

In another obscure citation, on the last years of Basque-Aquitanian independence the Frankish Continuations of the Chronicle of Fredegar make another reference to the Basques dwelling to the south of the Garonne, "qui antiquitus vocati sunt Vaccei." The Cosmographia (7-8th centuries) calls the Ile de Ré and Oleron, located off the Charente coast, the "Vacetae Insulae" or Vacetian Islands, where the Vacetae are Vascones by another name. That name is confirmed in the Continuations (''Pseudo-Fredegar'').

No clear boundary is cited on the north until 769, when the river Garonne is mentioned as setting the northern boundary for the Vascones at the end of the Franco-Aquitanian war, when the Basque lords and their duke Lupus crossed the Garonne to the Frankish fortress of Fronsac, near Bordeaux, to pledge allegiance to Charlemagne ("Ibi Vascones qui ultra Garonna commorantur ad eius praesentia venerunt"). Important is here the absence of a comma, in a text where commas are used. In the Vita Pardulfi, the author makes a distinction between Partes Aquitaniae and Vasconia for the mid-8th century, pinpointing Limoges in the former, but no other data are provided for other towns like Agen, Saintes, Perigord, or Bordeaux. From previous records, e.g. the 587 military campaigns, Toulouse is considered to lie out of Vasconia.

A conservative approach pinpoints the border of the Duchy on the Garonne before 769. However, based on the above leads and admittedly inferring my hypothesis ex silentio for some regions, it can be postulated that the general area of Vasconia, home to ethnic Basques or related peoples, may have included up to 768 a threshold at the north extending to the Ile de Ré and Oléron, Saintes, Bordeaux, Agenais, and possibly Perigord and Cahors. All that added to the rest of the lands south of the Garonne. Obviously, the demographic reality of those towns and their hinterland was not static, towns were probably awash in Gallo-Roman culture, and a receding Basque presence and progressive assimilation to the Gallo-Roman culture can be postulated until 768. After that year, they may have come to be considered numerically and politically irrelevant north of the Garonne river, and not mentioned anymore.

The Duchy of Vasconia comprised intermittently lands south of the Pyrenees, at least until the definite detachment of Pamplona from the Duchy in 824. It seems safe to assume that until the Carolingian penetration in Vasconia at the turn of the 9th century (778-806) the Basque duchy extended south across the Pyrenees onto its upper valleys, where it met the Andalusian military outposts. A southern buffer zone was provided on the pre-Pyrenean valleys by a fluctuating line of strongholds connecting Aibar, Leire, Jaca (-Loarre), Boltaña, Graus, Roda and Ager (upper Pallars). Cerdanya, probably inhabited by Basques in the early 8th century, is well known to have been in Uthman-ibn-Naissa's hands up to Abd ar-Rahman al Gafiqi's expedition in 731, when he defeated the former and subdued the region for the Umayyads. In 816 Basques, "qui trans Garonnam et circa Pyrineum montem habitant" rebelled on their territory against the deposition of their duke (according to Einhard). Aznar Sanchez, duke (count) of Hither Vasconia, was sent quash the rebellion in Pamplona in 824. It goes without saying, the fact that he was sent from the "hither" implies that there was a "thither", and that may have applied to the territory lying to the south-west of the Pyrenees (cf. unspecified "Hispani Vascones" on the 778 campaign to Saragossa).

Back in the 7th century, Basques are often cited in the territory of ancient Cantabria as fighting the Visigoths trying to subdue them. No dukes or warlords are cited leading them, and their political affiliation is not specified in the 6th and 7th centuries, but the archaeological lead—findings of Aldaieta, San Pelayo, "Visigothic" (sic!) cemetery of Pamplona, etc.—and scarce documental evidence point to a clear trans-Pyrenean, Merovingian connection. Not only that, as suggested by unearthed evidence the lands to the south of the Alavese Plains may have played host to a military buffer zone between the southern Visigoths and the Basques organized in an unspecified polity. This possibility confirms a west-east frontier line extending all the way to a fortification line in Navarre attested since the 9th-century, such as Monjardín—called "Deio" at the time of the first Navarrese kings—Olite, Aibar (Oibar), and on to the east into Cinco Villas in Aragon.

At the time of a Pamplonese rebellion against the Umayyad rule at the turn of the 9th century, a so-called Belasko al-Glaski (originary from present-day Gascony), "enemy of [Muslim] God", is cited as leading a pro-Frankish revolt taking over the Basque town. Ibn-Atsir clearly states that he was the son of Adalric, a Basque lord acting under command of the Duke of Vasconia in the vicinity of the river Garonne circa 785.

However, that territory is not delimited clearly, and undergoes an initial expansion up to the mid-8th century followed by a gradual shrinking and disintegration period up to 1058—annexation by Aquitaine. The Frankish king Dagobert I made in 628 arrangements for his brother Charibert II to rule over the territories between the Loire and the Pyrenees (''limes Spaniae'') 'in the general area of Vasconia', including Saintes, Perigueux, Cahors, Agenais, etc.

Furthermore, in the following years, the same king is reported to have subdued the whole Vasconia, beyond the Pyrenees too. This period, late 620s to early 670s, bears witness to Saint Amandus' failed attempt to convert the Basques to Christianity and his visit to an episcopal see across the Pyrenees, thought to be Pamplona in Frankish hands. During the same period Basque raids descending from north of the Pyrenees are attested in Visigothic records, attacking even Saragossa. It's known too that no representative of Pamplona attended the Councils of Toledo from 589 until 684.

The Ravenna Cosmographer calls "Vasconia" to the whole territory extending north up to the Loire river during the years of Basque-Aquitanian independence (660-768), so do the Continuations of the Chronicle of Fredegar, suggesting that it lies right across the Loire river. Some authors have put down this expansion of the name so far north to the Frankish negative propaganda in order to disrepute Aquitaine, inasmuch as the Basques were regarded as rustic, non-Romanized people. It seems more plausible the existence of a significant Basque component in central Aquitaine besides Gascony, rather than a single territory to the south of the Loire inhabited by Basques or under their rule. Adding to the confusion, the Basque troops were at the core of the Aquitanian army and deployed all over Vasconia and Aquitaine, even darting out of the territory, e.g. expeditions against Peppin on the siege of Narbonne in 754 and Peppin's Burgundy and Narbonne in 762.

In another obscure citation, on the last years of Basque-Aquitanian independence the Frankish Continuations of the Chronicle of Fredegar make another reference to the Basques dwelling to the south of the Garonne, "qui antiquitus vocati sunt Vaccei." The Cosmographia (7-8th centuries) calls the Ile de Ré and Oleron, located off the Charente coast, the "Vacetae Insulae" or Vacetian Islands, where the Vacetae are Vascones by another name. That name is confirmed in the Continuations (''Pseudo-Fredegar'').

| The Baigorri Valley in Lower Navarre lies on the southern fringes of the late Roman province of Novempopulania, but shared close ties with the valley of Baztan, probably also included in the Duchy of Vasconia at least until the turn of the millenium Credit: Iñaki LLM |

|

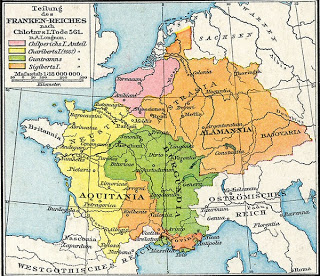

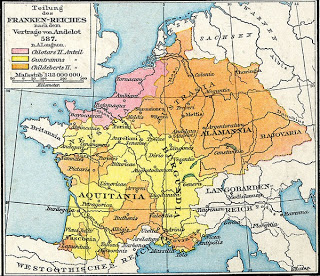

| At the time depicted (561), Novempopulania, here called with anticipation Vasconia, was uncharted territory for the Franks. Note that the dotted line over the Pyrenees remains just a geographical reference Credit: Maproom |

|

| In 587 duke of Toulouse Bladastes and Gallo-Roman duke Desiderius led an expedition against the Basques, they were defeated and killed Credit: Maproom |

A conservative approach pinpoints the border of the Duchy on the Garonne before 769. However, based on the above leads and admittedly inferring my hypothesis ex silentio for some regions, it can be postulated that the general area of Vasconia, home to ethnic Basques or related peoples, may have included up to 768 a threshold at the north extending to the Ile de Ré and Oléron, Saintes, Bordeaux, Agenais, and possibly Perigord and Cahors. All that added to the rest of the lands south of the Garonne. Obviously, the demographic reality of those towns and their hinterland was not static, towns were probably awash in Gallo-Roman culture, and a receding Basque presence and progressive assimilation to the Gallo-Roman culture can be postulated until 768. After that year, they may have come to be considered numerically and politically irrelevant north of the Garonne river, and not mentioned anymore.

The Duchy of Vasconia comprised intermittently lands south of the Pyrenees, at least until the definite detachment of Pamplona from the Duchy in 824. It seems safe to assume that until the Carolingian penetration in Vasconia at the turn of the 9th century (778-806) the Basque duchy extended south across the Pyrenees onto its upper valleys, where it met the Andalusian military outposts. A southern buffer zone was provided on the pre-Pyrenean valleys by a fluctuating line of strongholds connecting Aibar, Leire, Jaca (-Loarre), Boltaña, Graus, Roda and Ager (upper Pallars). Cerdanya, probably inhabited by Basques in the early 8th century, is well known to have been in Uthman-ibn-Naissa's hands up to Abd ar-Rahman al Gafiqi's expedition in 731, when he defeated the former and subdued the region for the Umayyads. In 816 Basques, "qui trans Garonnam et circa Pyrineum montem habitant" rebelled on their territory against the deposition of their duke (according to Einhard). Aznar Sanchez, duke (count) of Hither Vasconia, was sent quash the rebellion in Pamplona in 824. It goes without saying, the fact that he was sent from the "hither" implies that there was a "thither", and that may have applied to the territory lying to the south-west of the Pyrenees (cf. unspecified "Hispani Vascones" on the 778 campaign to Saragossa).

Back in the 7th century, Basques are often cited in the territory of ancient Cantabria as fighting the Visigoths trying to subdue them. No dukes or warlords are cited leading them, and their political affiliation is not specified in the 6th and 7th centuries, but the archaeological lead—findings of Aldaieta, San Pelayo, "Visigothic" (sic!) cemetery of Pamplona, etc.—and scarce documental evidence point to a clear trans-Pyrenean, Merovingian connection. Not only that, as suggested by unearthed evidence the lands to the south of the Alavese Plains may have played host to a military buffer zone between the southern Visigoths and the Basques organized in an unspecified polity. This possibility confirms a west-east frontier line extending all the way to a fortification line in Navarre attested since the 9th-century, such as Monjardín—called "Deio" at the time of the first Navarrese kings—Olite, Aibar (Oibar), and on to the east into Cinco Villas in Aragon.

At the time of a Pamplonese rebellion against the Umayyad rule at the turn of the 9th century, a so-called Belasko al-Glaski (originary from present-day Gascony), "enemy of [Muslim] God", is cited as leading a pro-Frankish revolt taking over the Basque town. Ibn-Atsir clearly states that he was the son of Adalric, a Basque lord acting under command of the Duke of Vasconia in the vicinity of the river Garonne circa 785.

|

| Reproduction of thatched circular houses in the Iron Age settlement of Henaio on top of a hill near Dulantzi, Álava, probably not very different from the ones inhabited in the rural milieu after the fall of the Roman Empire Photo: Iñaki LLM |

SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

The foundations of Vasconia's social structure lie on a blend of Basque primitive society and Roman influences. Urban centres, i>villae and mansions dotted the Vasconia, and it is thought that local Basque lords engaged in a synergy by which they provided for the defense of local Gallo-Roman or Hispano-Roman magnates and their holdings, while sticking to their separate autochthonous organization in the hinterland and mountains.

The Basque tribes shared common bonds and were organized in valleys interconnected by mountain passes and paths, commonly used by humans and cattle in their grazing and the seasonal migrations. The uplands were a safer place to live than down the valley, and that was the place where the Basques asserted their internal cohesion. Life among the Basques provided shelter, a sense of community and solidarity, and capacity to strike back when alien hosts or armies broke in.

The Basque tribes shared common bonds and were organized in valleys interconnected by mountain passes and paths, commonly used by humans and cattle in their grazing and the seasonal migrations. The uplands were a safer place to live than down the valley, and that was the place where the Basques asserted their internal cohesion. Life among the Basques provided shelter, a sense of community and solidarity, and capacity to strike back when alien hosts or armies broke in.

The basic institution to a valley was the batzar or biltzar, a popular assembly held probably in a landmark of religious significance where current matters were discussed by all those attending. The assembly elected the most able person(s) to undertake a specific task. When wider regional action was required, the representatives attended meetings where provisions for military or economic arrangements were decided. When the meetings involved a few neighbouring valleys, the representatives may have met on mountains passes, probably on sites where significative megalithic monuments stood and the agreements could be sealed on the "presence" of common tribal ancestors. These representatives gradually became one and the same person, chieftains, who between the late 8th and 11-12th centuries would raise to become lords, amass some wealth and create a lineage. During this later period, these tribal leaders were linked to the foundation of monasteries, establishing an oath of allegiance to overlords, be they dukes, princes or kings, who in turn acknowledged his/her right over a holding—lands, orchards, mill, etc. Monasteries were basically extensions of certain political centre, and carriers of a culture and a aesthetic affiliation.

There is evidence in the 8th century of meetings where lords from northern regions of Vasconia gathered near Bordeaux to decide on matters that demanded shared decisions. At this point of history, ahead of Charlemagne's signature monastery foundations with the imprint of Benedict of Aniane, a layer of Christian ceremonial elements hid a synchretic pagan reality.

Unlike neighbouring regions, counts didn´t play a role in Vasconia's power share (7-8th centuries). Moreover, they were absent, and dukes are mentioned as the main figures of the Basques, immediately followed on the hierarchy by tribal chieftains and families who owed obedience to the duke, at least until the rise of the Carolingian dynasty. The grip of the Duke of Vasconia on the Basques was tighter or looser depending on the historic circumstances, with the extent of his rule sometimes being just nominal in the farther away areas, but a real one in the closest ones.

Some authors hang onto this evidence to point out that in this period the unruly Basques started their expansion north, even if locals from Novempopulania didn't oppose them. Furthermore, Aquitanian name inscriptions of the Roman times point to the contrary, and in the late years of the Roman Empire the establishment of a separate province for the proper Aquitanians, different from the Gauls of Celtic stock, is celebrated in an inscription on a slab in the village of Hasparren (15 km south of Bayonne). The Basques are reported to have raided the plains, looted them, and getting back to the mountains with prisoners, and not extending north.

In 589, the bishop of Pamplona (Iruñea) attended the Church Councils of Toledo, meaning that at that point the town remained under Visigoth rule, but in 593 no representative attended, meaning it wasn´t probably in Visigoth hands or its status was unstable. The semi-legendary duke of Cantabria Francio is reported to be paying tribute to the Franks just about this period and later ("provinciam Cantabriam..., quam aliquando Franci possederant", according to the Pseudo-Fredegar). The archaeological findings in Aldaieta and San Pelayo (vicinity of Vitoria-Gasteiz) cited earlier in this page bear witness to a Merovingian or Aquitanian type of settlement and burial tradition that would support the Frankish chronicler's assertion.

The history of the Duchy is divided into 4 stages:

4. VASCONIA TOWARDS GASCONY (864-1058)

The basic institution to a valley was the batzar or biltzar, a popular assembly held probably in a landmark of religious significance where current matters were discussed by all those attending. The assembly elected the most able person(s) to undertake a specific task. When wider regional action was required, the representatives attended meetings where provisions for military or economic arrangements were decided. When the meetings involved a few neighbouring valleys, the representatives may have met on mountains passes, probably on sites where significative megalithic monuments stood and the agreements could be sealed on the "presence" of common tribal ancestors. These representatives gradually became one and the same person, chieftains, who between the late 8th and 11-12th centuries would raise to become lords, amass some wealth and create a lineage. During this later period, these tribal leaders were linked to the foundation of monasteries, establishing an oath of allegiance to overlords, be they dukes, princes or kings, who in turn acknowledged his/her right over a holding—lands, orchards, mill, etc. Monasteries were basically extensions of certain political centre, and carriers of a culture and a aesthetic affiliation.

There is evidence in the 8th century of meetings where lords from northern regions of Vasconia gathered near Bordeaux to decide on matters that demanded shared decisions. At this point of history, ahead of Charlemagne's signature monastery foundations with the imprint of Benedict of Aniane, a layer of Christian ceremonial elements hid a synchretic pagan reality.

Unlike neighbouring regions, counts didn´t play a role in Vasconia's power share (7-8th centuries). Moreover, they were absent, and dukes are mentioned as the main figures of the Basques, immediately followed on the hierarchy by tribal chieftains and families who owed obedience to the duke, at least until the rise of the Carolingian dynasty. The grip of the Duke of Vasconia on the Basques was tighter or looser depending on the historic circumstances, with the extent of his rule sometimes being just nominal in the farther away areas, but a real one in the closest ones.

|

| The salt pond terraces of Añana-Gesaltza. The technique and the landscape have remained almost unaltered since Roman times. Credit: Jsanchezes |

|

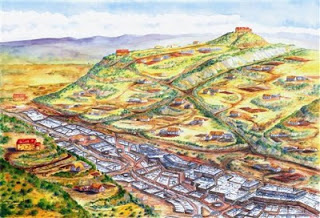

| Depiction in hindsight of the 9th century Añana-Gesaltza saltwork complex Credit: Fund. Valle Salado |

Hence the allegiance to the Duke was increasingly loose and theoretical after the late 8th century, and especially the late 9th century, with local leaders acting increasingly as the sole rulers over small regional domains, such as appanages, counties and small realms developed within a dismembering Vasconia. As for the judiciary system, nor the Visigoth law neither the Roman law seem to have been in use in the Duchy of Vasconia, and a native order appears to have prevailed until the Carolingian takeover in 768-769.

As of 781, Charlemagne started appointing counts (Bordeaux, Toulouse, Fezensac) on the bordering lands of Vasconia along the banks of the river Garonne, so undermining the grip on power of the dukes of Vasconia. Despite the Carolingian decline and territorial partition after their dynastic wars (mainly feuds between Charles the Bald, Pepin II and Lothair), the lineage of independent dukes of Vasconia rising to prominence after 864 didn´t reinforce their grip over all other local magnets, instead distributing their lands among their offspring and establishing counties that led to the creation of a myriad of small autonomous political entities (Comminges, Astarac, etc.), in a way that the title of Duke of Vasconia afforded a very limited political power during most of the 10 and 11th century, the facto lying in the hands of the counts.

As of 781, Charlemagne started appointing counts (Bordeaux, Toulouse, Fezensac) on the bordering lands of Vasconia along the banks of the river Garonne, so undermining the grip on power of the dukes of Vasconia. Despite the Carolingian decline and territorial partition after their dynastic wars (mainly feuds between Charles the Bald, Pepin II and Lothair), the lineage of independent dukes of Vasconia rising to prominence after 864 didn´t reinforce their grip over all other local magnets, instead distributing their lands among their offspring and establishing counties that led to the creation of a myriad of small autonomous political entities (Comminges, Astarac, etc.), in a way that the title of Duke of Vasconia afforded a very limited political power during most of the 10 and 11th century, the facto lying in the hands of the counts.

HISTORY

- Genesis

The Basques had been last depicted as a Romanized even Christianized people (cf. Prudentius, early 5th century) living on the banks of the middle stage of river Ebro and north, in current Navarre, lower Rioja and part of Aragon. In the last centuries of the Roman Empire, widespread uprisings brought about by social dissatisfaction erupted in the area delimited by the rivers Ebro, Rhone and Brittany. Bishop and chronicler Hidatyus was well aware of the existence of the "Vasconias", but he doesn't associate the Bagaudae rebels with the Basques anyway.

Since Hydatius' death (469) until 581 nothing is heard about the Basques. That year Visigoth king Liuvigild submits the Basques ("partes Vasconiae"), certainly takes over Pamplona (called Iruñea by the locals) and founds the fortress called Victoriacum (dubiously current Vitoria-Gasteiz, but possibly Iruña-Veleia).

The count Galactorius of Bordeaux is cited circa 580 as having fought the Basques and the Cantabri, who are reported conducting their attacks from the mountains. Starting in 581, both the Goths and the Franks respectively launched major campaigns against the Basques. In 587 Basques are cited as raiding the plains of Aquitaine, possibly to the west of Toulouse. The Frank Chilperic I sent over his duke Bladastes, stationed in that city, and the Gallo-Roman duke of Aquitaine Desiderius, who were both defeated. The Basques in turn are reported to have carried cattle and prisoners back to their hideouts in the mountains.

| Bridge of Trespuentes spanning river Zadorra across ancient Iruña-Veleia, possible location of the Victoriacum cited by the Visigoths (581). It lies on the Bordeaux - Astorga, a major Early Medieval communication line |

Some authors hang onto this evidence to point out that in this period the unruly Basques started their expansion north, even if locals from Novempopulania didn't oppose them. Furthermore, Aquitanian name inscriptions of the Roman times point to the contrary, and in the late years of the Roman Empire the establishment of a separate province for the proper Aquitanians, different from the Gauls of Celtic stock, is celebrated in an inscription on a slab in the village of Hasparren (15 km south of Bayonne). The Basques are reported to have raided the plains, looted them, and getting back to the mountains with prisoners, and not extending north.

|

| The Urkulu watchtower, built up to celebrate Roman victory over the Aquitanians, was reused as a Medieval fortress, straddling the western Pyrenees Credit: Iñaki LL |

The history of the Duchy is divided into 4 stages:

1. DUCHY OF VASCONIA: Early Merovingian Period (602-660)

2. VASCONIA, Independent with Aquitaine (660-769)

3. CAROLINGIAN VASCONIA (769-864)4. VASCONIA TOWARDS GASCONY (864-1058)

FURTHER READING

1. Collins, Roger. 1990. The Basques. Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17565-2.

2. Euskomedia Fundazioa. Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia

2. Euskomedia Fundazioa. Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia

3. Lewis, Archibald R. 1965. Expansion into Gascony and Catalonia. The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718-1050. University of Texas Press.

- Vasconia, Independent With Aquitaine (660-769)

The Basques were brought to heel in 635 after a gigantic Franco-Burgundian expedition. The Basque leaders vowed loyalty to Frankish king Dagobert I, but after his death the Merovingian dynasty sank in a steady decline started with the so-called rois...

- Siege Of Narbonne (752-759)

The Siege of Narbonne took place between 752 and 759 led by the Frankish king Pepin the Short against the Muslim stronghold defended by an Umayyad garrison and its Gothic and Gallo-Roman inhabitants. The siege remained as a key battlefield in the context...

- Battle Of Toulouse (721)

The Battle of Toulouse (721) was a victory of an Aquitanian Christian army led by the duke Odo of Aquitaine over an Umayyad Muslim army besieging the city of Toulouse, and led by the governor of Al-Andalus, Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani. The victory checked...

- Newport?s Medieval Ship Could Have Been Basque

The origins of the Newport Medieval Ship may have finally been solved ? with new research announced yesterday pointing to the north of Spain. Thanks to recent advances in tree-ring dating, experts have obtained the first scientific evidence that...

- Catching Up On Some Posts

The following (or in this case I suppose are preceding) are catch up posts: LAST CALL FOR PAPERS The End of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse, the Rise of the Franks, and the 'Beginning of France': A Symposium on the Occasion of the 1500th Anniversary...

.