Medieval History

.

VASCONIA, Independent with Aquitaine (660-769)

The Basques were brought to heel in 635 after a gigantic Franco-Burgundian expedition. The Basque leaders vowed loyalty to Frankish king Dagobert I, but after his death the Merovingian dynasty sank in a steady decline started with the so-called rois faineants, the rise of the mayors of the palace, and a crisis of Frankish royal authority. The Franks were far north-east fighting each other, held feeble military strength in the region, and they were considered culturally inferior as compared to the prevailing Aquitanian Gallo-Roman civilization. The circumstances sparked the emergence of a strategic alliance between Aquitanian Gallo-Roman magnates and Basque military leaders.

In the year 660, Felix of Aquitaine, a patrician of Gallo-Roman stock from Toulouse, received the ducal title of both Vasconia and Aquitaine (the latter located between the Garonne and Loire rivers), effectively ruling independently over Vasconia and at least part of Aquitaine. Under Felix and his successors, Frankish overlordship became merely nominal. Aquitaine-Vasconia became an important regional power. Independent dukes Lupus, Odo, Hunald and Waifer succeeded him respectively, with the last three belonging to the same lineage.

The ethnicity of these dukes is not certain, since records are not conclusive. Franks had prevailed in Aquitaine up to 660, small Frankish communities had settled in southern Aquitaine (attested between Toulouse and Carcassone, etc.) and Provence, but in no way were they prevalent and may have been assimilated by the prevailing Gallo-Roman culture, if not by Basque influence in bordering areas. Odo is a Frankish name, but Latin name Lupus (cited as Lop, Lope,...) probably hides a Basque Otsoa (='wolf', cf. Aznar, Belasko), made later into a surname, e.g. Otsoa, Otxoa, Ochoa, Diaz de Ochoa, Ochoa de Olza, etc.

Despite their styling as rulers over Vasconia and Aquitaine, the real range of action of the dukes is open to debate, since we hardly ever hear of them acting south of the Garonne, except in quest of shelter among the Basques. But for Jean de Jaurgain's citation of Odo as fighting in Pamplona (no primary source provided), they are attested as acting around and to the north of the river Garonne, e.g. in 732 (or 733) Abd ar-Rahman al-Gafiqi's expedition was not engaged in open pitch battle by a military force before Bordeaux, just local ineffective resistance, while the Basque town of Auch is thought to have been largely abandoned, ravaged and burnt down.

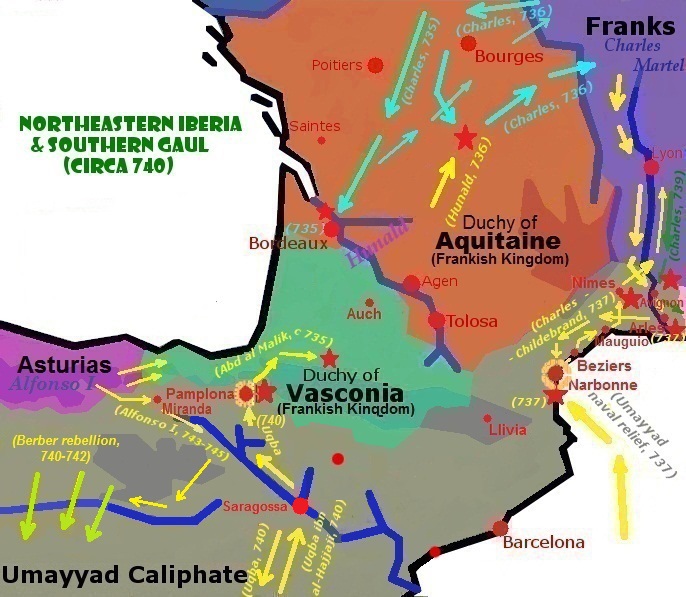

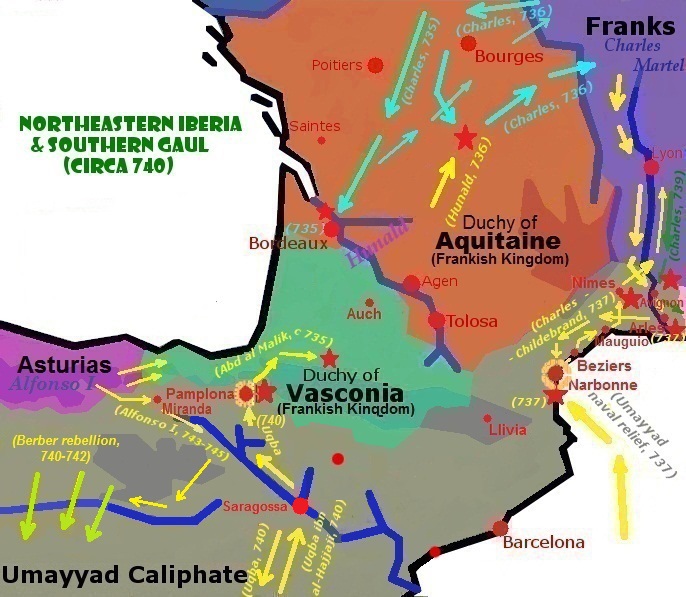

After Abd ar-Rahman's defeat, in approx. 735 Abd al-Malik is not reported to be engaging Odo's or Hunald's troops (who were busy fending off Charles' thrust in Aquitaine anyway), but "Christian" inhabitants across the Pyrenees. This leads us to think that Vasconia was actually loosely tied to the rule of the duke, possibly based on a mutually beneficial treaty whereby the Basques provided military (and fiscal) support to the duke, while the Basques were left to arrange their self-government on a tribal basis. (See The Duchy of Vasconia in this blog)

At about 670, Lupus I was proclaimed duke in Toulouse, a lord of probable Basque stock. In Hispania, just after his proclamation as king in Toledo, Wamba headed north to fight the Basques in Cantabria, an imprecise territory with unknown ties to the duchy of Vasconia. The Basques of that area were defeated, a triumph of the Visigoth king narrated by Isidore of Seville with literary praise and exaggeration.

A period of obscurity followed this campaign in "Cantabria", no further news are revealed in the ensuing period, but a regional march (mark) answerable to Toledo may have been established. Whether it was precisely a duchy or not, is not revealed, but the next piece of news sheds some light. A certain duke Pedro of Cantabria is cited at circa AD 737, whose son Alfonso married Asturian leader Pelagius' daughter Ermenesinda to form a sole principality under their rule. The creation of such title, duke, could have only taken place before the Umayyad conquest, and may make reference to its corresponding territorial entity, a duchy.

When he was done in Cantabria, Wamba heard of a rebellion in Gothic Septimania that received the military support of the Basque duke Lupus. Wamba then undertook an expedition east, crossed the Pyrenees over Cerdanya on the east, and directed his military force to Auch first, then to Septimania. Wamba is said to have revamped Pamplona's walls after quelling the Septimanian uprising in 674.

It's therefore fairly safe to assume that Visigoths ruled during the following years in Pamplona and across the whole Ebro basin. In 684 and 693 we hear of Pamplonese bishops attending the Councils of Toledo, but nothing is known about their attendance of the 702 Council, since the documents issued in this controversial Council vanished. In this respect, an improvement as it is over other traditional maps (with almost 20th century administrative borders!), Auñamendi's map doesn't possibly hold water on the light of the latest historic research.

Circa 735, Odo died, leaving his realm to his son Hunald, who desiring the former independence challenged Charles's overlordship. Charles in turn marched over Bordeaux in 735, captured the city and in his way plundered much of northern Aquitaine, churches and monasteries inclusive. He came back in 736, this time to face the resistance of the Aquitanian counts led by Hunald, who engaged him in battle, while the exact location is not known. The outcome of the battle seems to have been beneficial for Hunald, who got a deal whereby Aquitaine's autonomy was respected in exchange for formal suzerainty to Charles. Charles did not remain in Aquitaine for long, and the Frankish leader headed south-east via the Rhone Valley to settle matters in Burgundy (i.e. impose his own followers in key positions) and fight in Septimania and Provence. Hunald abdicated circa 744 to his son Waifer, and may have retired to a monastic life on the Isle of Ré.

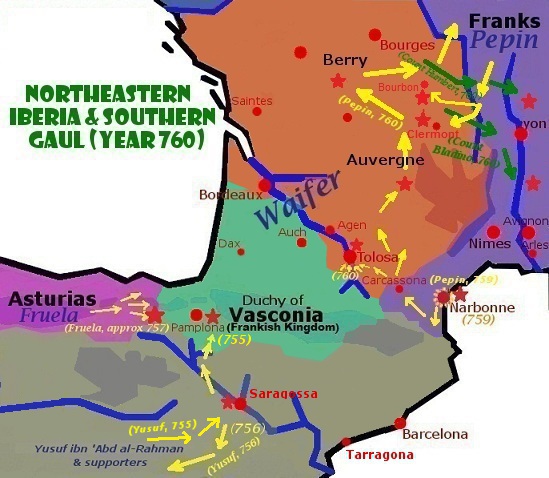

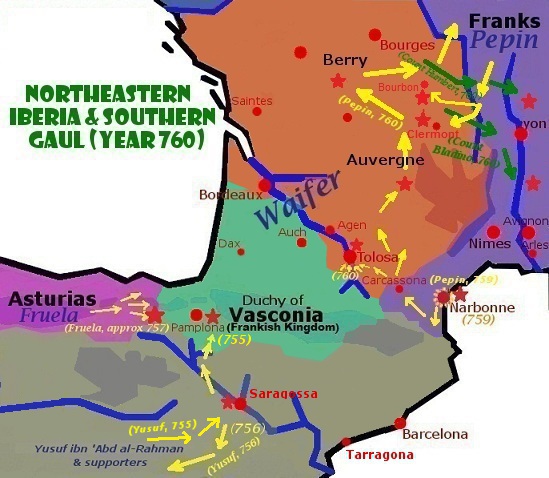

Peace with the Carolingian central power was flimsy and we hear of Waifer and his Basque army attacking Pepin the Short while on his siege to Narbonne circa 754. After his campaign against the Muslims in Septimania (conquest of Narbonne, 759) and the allegiance of its Visigoth nobles, the Frankish leader-turned-king could now concentrate all his attention in subduing Aquitaine.

After bringing to heel Septimania (759), the Frankish Pepin the Short unleashed a devastating war on Aquitaine as south as the Garonne on its final stage that was to have dire consequences on its population, towns and society. Waifer and his Basque troops confronted the Frankish king several times across Aquitaine, but were defeated thrice in 760, 762, and the Basques were badly defeated in 766-67, after which the Basque lords saw no option but come over to Agen and pledge loyalty to Pepin. Waifer in turn, battered by the defeats, was eventually murdered by one of his followers at the instigation (paid, according to some sources) of Pepin.

However, his son Hunald (II) rose up against the Franks, this time led by king Charlemagne after Pepin´s 768 death. Hunald II opted to flee and take refuge south of the Garonne, but at this point we know of a duke of Vasconia, Lupus II, other than the Aquitanian one. Despite providing initially shelter to his ally and rebel Hunald, Lupus backed down on his support and handed him over to Charlemagne out of fear of his military might (Charlemagne actually crossed the Garonne south). The Basque lords submitted in 769 to the Carolingian king (Fronsac < Franciacus, near Bordeaux). The Basque-Aquitanian sovereignty was over.

- Vasconia: Early Merovingian Period (602-660)

Prehistoric megalithic monuments like this, mainly dolmens and cromlechs, were important landmarks erected at crossroads and mountain passes. Still in the Early Medieval Ages, representatives of neighbouring tribes and valleys honoured their ancestors...

- Siege Of Narbonne (752-759)

The Siege of Narbonne took place between 752 and 759 led by the Frankish king Pepin the Short against the Muslim stronghold defended by an Umayyad garrison and its Gothic and Gallo-Roman inhabitants. The siege remained as a key battlefield in the context...

- The Duchy Of Vasconia: Extent And Organization

The Duchy of Vasconia (or Wasconia) was initially (AD 602) a polity created by the Franks aimed at holding sway over the Basques. The first dukes appointed were of Germanic stock, but Vasconia was far away from the Frankish heartland and despite its suzerainty...

- Newport?s Medieval Ship Could Have Been Basque

The origins of the Newport Medieval Ship may have finally been solved ? with new research announced yesterday pointing to the north of Spain. Thanks to recent advances in tree-ring dating, experts have obtained the first scientific evidence that...

- Catching Up On Some Posts

The following (or in this case I suppose are preceding) are catch up posts: LAST CALL FOR PAPERS The End of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse, the Rise of the Franks, and the 'Beginning of France': A Symposium on the Occasion of the 1500th Anniversary...

Medieval History

INDEPENDENT VASCONIA AND AQUITAINE UNITED

In the year 660, Felix of Aquitaine, a patrician of Gallo-Roman stock from Toulouse, received the ducal title of both Vasconia and Aquitaine (the latter located between the Garonne and Loire rivers), effectively ruling independently over Vasconia and at least part of Aquitaine. Under Felix and his successors, Frankish overlordship became merely nominal. Aquitaine-Vasconia became an important regional power. Independent dukes Lupus, Odo, Hunald and Waifer succeeded him respectively, with the last three belonging to the same lineage.

The ethnicity of these dukes is not certain, since records are not conclusive. Franks had prevailed in Aquitaine up to 660, small Frankish communities had settled in southern Aquitaine (attested between Toulouse and Carcassone, etc.) and Provence, but in no way were they prevalent and may have been assimilated by the prevailing Gallo-Roman culture, if not by Basque influence in bordering areas. Odo is a Frankish name, but Latin name Lupus (cited as Lop, Lope,...) probably hides a Basque Otsoa (='wolf', cf. Aznar, Belasko), made later into a surname, e.g. Otsoa, Otxoa, Ochoa, Diaz de Ochoa, Ochoa de Olza, etc.

Despite their styling as rulers over Vasconia and Aquitaine, the real range of action of the dukes is open to debate, since we hardly ever hear of them acting south of the Garonne, except in quest of shelter among the Basques. But for Jean de Jaurgain's citation of Odo as fighting in Pamplona (no primary source provided), they are attested as acting around and to the north of the river Garonne, e.g. in 732 (or 733) Abd ar-Rahman al-Gafiqi's expedition was not engaged in open pitch battle by a military force before Bordeaux, just local ineffective resistance, while the Basque town of Auch is thought to have been largely abandoned, ravaged and burnt down.

After Abd ar-Rahman's defeat, in approx. 735 Abd al-Malik is not reported to be engaging Odo's or Hunald's troops (who were busy fending off Charles' thrust in Aquitaine anyway), but "Christian" inhabitants across the Pyrenees. This leads us to think that Vasconia was actually loosely tied to the rule of the duke, possibly based on a mutually beneficial treaty whereby the Basques provided military (and fiscal) support to the duke, while the Basques were left to arrange their self-government on a tribal basis. (See The Duchy of Vasconia in this blog)

> |

Remains of a Roman road in Besaya (Cantabria), near the Ebro headwaters, a buffer zone inhabited by Basques and home to continuous battles with the Visigoths during the early Middle Ages Photo: Angelito 86 |

A period of obscurity followed this campaign in "Cantabria", no further news are revealed in the ensuing period, but a regional march (mark) answerable to Toledo may have been established. Whether it was precisely a duchy or not, is not revealed, but the next piece of news sheds some light. A certain duke Pedro of Cantabria is cited at circa AD 737, whose son Alfonso married Asturian leader Pelagius' daughter Ermenesinda to form a sole principality under their rule. The creation of such title, duke, could have only taken place before the Umayyad conquest, and may make reference to its corresponding territorial entity, a duchy.

When he was done in Cantabria, Wamba heard of a rebellion in Gothic Septimania that received the military support of the Basque duke Lupus. Wamba then undertook an expedition east, crossed the Pyrenees over Cerdanya on the east, and directed his military force to Auch first, then to Septimania. Wamba is said to have revamped Pamplona's walls after quelling the Septimanian uprising in 674.

It's therefore fairly safe to assume that Visigoths ruled during the following years in Pamplona and across the whole Ebro basin. In 684 and 693 we hear of Pamplonese bishops attending the Councils of Toledo, but nothing is known about their attendance of the 702 Council, since the documents issued in this controversial Council vanished. In this respect, an improvement as it is over other traditional maps (with almost 20th century administrative borders!), Auñamendi's map doesn't possibly hold water on the light of the latest historic research.

THE MUSLIMS BREAK INTO VASCONIA

In 711 the Visigoth king Roderic was fighting the Basques in Pamplona, but diverted his attention to the new foe coming from Africa. It seems easier to assume that the Basques were in command of the position and the Visigothic king was on the gates of the fortress, since he headed south on hearing the news of an invasion. Jean de Jaurgain cites Odo as fighting the Visigoth king in the Basque stronghold, but doesn´t provide a primary source.

In 714, new peoples and civilizations arrive in Basque territory from the south: Berbers and Arabs of Muslim religion. Islam, a faraway but ever changing civilization was not well known, but shared important common values with the Christians, especially with unitarian Christians. They were all of a Semitic background, both revered Jesus, were People of the Book and worshiped a single God. During at least two centuries Islam was still held by Church officials as a deviated version of Christianity brought from Africa, the Koran hadn´t even been drawn up as we know it today. While original Arabs were not a very sophisticated people, their expanding empire enriched substantially on Middle Eastern and Persian administrative elements picked up and integrated into their civilization, especially after the Umayyads made Damascus their capital (661).

On the other hand, Basques hang primarily onto polytheist practices, superficially Christianized. During this period and the next century, Basques are described by the Muslims as being pagans for the most part, as pointed out by Jimeno Jurio. Basques seem to have taken different positions towards the newcomers, who were settling down on both banks of the Ebro. In 714, Pamplona (called by locals Iruñea) surrendered to the Umayyads after reaching with the Umayyad commanders an agreement favourable to its inhabitants, probably respecting their laws and possibly conceding to some kind of self-government. A Berber garrison stationed out of the fortress, following the customary practice as it was during this initial conquest period of Hispania. The town flourished in turn as a springboard and base for the military expeditions to present-day Gascony.

Huesca also fell to the Umayyads after a seven year siege, according to the later Muslim geographer Ahmad ibn Umar al-Udri (1003-1085). The Arabs Banu Salama are said to have held the position with much displeasure to its inhabitants until it was liberated by Bahlul ibn Marzuq coming from Barbitania (800).

In 714, new peoples and civilizations arrive in Basque territory from the south: Berbers and Arabs of Muslim religion. Islam, a faraway but ever changing civilization was not well known, but shared important common values with the Christians, especially with unitarian Christians. They were all of a Semitic background, both revered Jesus, were People of the Book and worshiped a single God. During at least two centuries Islam was still held by Church officials as a deviated version of Christianity brought from Africa, the Koran hadn´t even been drawn up as we know it today. While original Arabs were not a very sophisticated people, their expanding empire enriched substantially on Middle Eastern and Persian administrative elements picked up and integrated into their civilization, especially after the Umayyads made Damascus their capital (661).

On the other hand, Basques hang primarily onto polytheist practices, superficially Christianized. During this period and the next century, Basques are described by the Muslims as being pagans for the most part, as pointed out by Jimeno Jurio. Basques seem to have taken different positions towards the newcomers, who were settling down on both banks of the Ebro. In 714, Pamplona (called by locals Iruñea) surrendered to the Umayyads after reaching with the Umayyad commanders an agreement favourable to its inhabitants, probably respecting their laws and possibly conceding to some kind of self-government. A Berber garrison stationed out of the fortress, following the customary practice as it was during this initial conquest period of Hispania. The town flourished in turn as a springboard and base for the military expeditions to present-day Gascony.

Huesca also fell to the Umayyads after a seven year siege, according to the later Muslim geographer Ahmad ibn Umar al-Udri (1003-1085). The Arabs Banu Salama are said to have held the position with much displeasure to its inhabitants until it was liberated by Bahlul ibn Marzuq coming from Barbitania (800).

By 720, Narbonne fell to the Umayyads and the Andalusian governor Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani was planning to tear his way into the Atlantic. From the Umayyad base of Narbonne, the first stronghold to be captured was Toulouse. In 721 a huge Muslim expedition invested the Aquitanian fortress and Odo fled for help. We hear that redoubtable Basque slingers fought along with the Muslims in the siege against the Aquitanians, who may have included Basques, since the duke had relied on them in previous campaigns on the Frankish civil wars ("Eodo, dux Aquitaniorum, commoto exercitu Wasconum"). Despite Charles' refusal to assist him, Odo came back with Aquitanian and Frankish reinforcements, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Andalusians and halted temporarily the Umayyad expansion.

By the late 720s, the Berber commander Utman ibn Naissa, "Munuza", was stationed in the Pyrenean Cerdanya. With its probable Basque population's collaboration, signed a treaty with the duke over Vasconia and Aquitaine Odo, who married his daughter Lampegia to the Berber leader, and became de facto detached from Umayyad Cordova. Utman ibn Naissa went on to kill the bishop of Urgell, an assassination that may have been interpreted as an act of disobedience by Cordovan officials, since the Visigothic Church held a secondary but important status in al-Andalus.

Meanwhile, the Basque-Aquitanian duke was trying to fend off Charles Martel's advances on the north. Charles crossed the Loire and ravaged northern Aquitaine two times in 731, capturing and sacking Bourges too. Odo in turn retook Bourges and engaged Charles' forces, but the duke was defeated by the strong Frankish army.

Cerdanya, a wide valley nestling on the slopes of the eastern Pyrenees, was home to Uthman ibn Naissa's garrison and his stronghold Llivia, but the Cordovan governor Abd ar-Rahman defeated them (731)

ahead of his famous expedition over Vasconia and Aquitaine Credit: Ensopegador

ahead of his famous expedition over Vasconia and Aquitaine Credit: Ensopegador

Meanwhile, the Basque-Aquitanian duke was trying to fend off Charles Martel's advances on the north. Charles crossed the Loire and ravaged northern Aquitaine two times in 731, capturing and sacking Bourges too. Odo in turn retook Bourges and engaged Charles' forces, but the duke was defeated by the strong Frankish army.

THE UMAYYADS OVERRUN VASCONIA

This state of things didn´t last long. Utman ibn Naissa, who had risen up against the Umayyad rule, was attacked by the new Andalusian wali (governor) Abdul Rahman al-Ghafiqi, captured Llivia, and put him to death. Vasconia was again open to the Umayyads and this time, in 732, an expedition crossed the Pyrenees northbound by the west via Pamplona. The Umayyad commander probably meant to consolidate his new position as commander-in-chief over Muslim Iberia, rallying rival groups and factions against a common enemy and strengthening internal cohesion by punishing Odo for his alliance with the Berber lord. The expedition rampaged its way through Vasconia, sacked Auch, and continued to Bordeaux.

In 732 Odo suffered in Bordeaux a major setback. The defenses of the Aquitanian city couldn´t hold back the Muslims troops (Arabs and Berbers) under Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, capturing and looting it. The Aquitanian duke engaged them on the outskirts a second time, but was utterly routed at the Battle of the River Garonne. However, Odo managed to escape with some troops, while the Umayyad expedition plundered its way towards Tours.

Odo saw no option but to ask for help and vow loyalty to his Frankish enemy, the Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia and Neustria ("Francia") Charles "Martel". Both forces together were then able to decisively defeat the Muslim raiders at the Battle of Poitiers in the Autumn of 732 (or 733 according to Roger Collins). Odo's forces formed the left wing of the Frankish forces, and dealt a decisive blow when they broke into the Umayyad main camp and set it on fire. Aquitaine and its attendant marches were then formally united to Francia, but Odo, almost in his 80s and enjoying widespread popularity in his realm, kept ruling the Duchy of Vasconia and Aquitaine about the same as before until his death (probably 735).

After the blow to the Umayyad expedition, many of the troops made their way back in disarray towards Narbonne using the axis of the Garonne river. Others may have fled down the same route they used to advance north. What we know is that by 734 a so-called Frankish (probably Basque-Aquitanian) party was established in Pamplona, so the wali (governor) of Al-Andalus Abd al-Malik ibn Katan al-Fihri headed north to recapture it, but unable to break their resistance, he left troops to invest the Basque fortress and decided to continue his way north across the Pyrenees, where he engaged the Basques in skirmishes and was eventually overcome in open battle, but managed to escape back to Al-Andalus. Circa 740, with Odo dead and with duke Hunald ruling over Vasconia, the wali Uqba ibn al-Hayyay (734-741), who was stamping out Berber revolts in Iberia and North Africa, had to head up the Ebro river to Pamplona to quash a rebellion, probably spurred by the defection of the local garrison to the Berber revolt. Uqba re-established order, imposed a new garrison, and direct Cordovan discipline in Pamplona.

It´s not far-fetched to think that in the run-up to the Berber withdrawal during 739-742, when Berber troops gave up their positions towards the south to join the North African and Iberian Berber rebellion, the south-western fringes of Basque populated territories (present-day north of Castile, Rioja, Álava, western Navarre) were in Andalusian hands. Then a campaign led by Alfonso I is recorded, who attacked and devastated a large territory between the Ebro and the Duero (possibly Iruña-Veleia too, on the banks of river Zadorra). In the wake of the power vacuum, it's not risky to assume that the Basques retrieved part of the land formerly watched by the Berber troops, e.g. Alavese Mountains, Alavese Valleys, hilly areas of La Rioja, Oca Mountains and fringes of Bureba.

On the other hand, the debate remains wide open as to the governance of coastal areas, since whatever is the conclusion, it is made ex silentio, i.e. sources are mute. A duke of Cantabria Peter is attested as father of Asturian king Alfonso I, who may have kept a swathe of hilly areas of former Cantabria, populated by Basques, out of Andalusian reach. The marriage to Pelagius' daughter may have expanded Asturian rule to the east (as of 739), possibly up to Encartaciones.

With regards to present-day Gipuzkoa and northern Navarre, they may have remained loosely tied to the Duchy of Vasconia (see extent and organization of the Duchy of Vasconia), governed semi-autonomously by its own people, but this can only be guessed at. Later territorial and ecclesiastic organization may clarify the bonds and allegiances established by this region, when the Sancta Trinitas hermitage and cave (known today as San Adrian, located at the foot of mountain Aizkorri on an important medieval route before descending to Álava) is cited as delimiting the south-western boundary of the Bayonne diocese (Oria valley) in the late 10th century. The linguistic lead (Basque dialectal distribution) may support this assumption too in that central dialects lay to the east, while the western dialects lie to the west (imaginary line drawn by the massifs of Aizkorri, Samiño-Izaspe, Izarraitz, Arno, coastline).

In 757, Fruela succeeded Alfonso I as king of Asturias, and his forces subdued the resisting western Basques in the upper Ebro, Álava and Biscay. The Asturian king brought back from Álava a Basque maid as prisoner, Munia, to become his wife. In 755 the last governor of Al-Andalus, Yusuf al Fihri, detoured an expedition to Saragossa to quash Basque unrest near Pamplona, resulting in the defeat of the Arab army.

Odo saw no option but to ask for help and vow loyalty to his Frankish enemy, the Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia and Neustria ("Francia") Charles "Martel". Both forces together were then able to decisively defeat the Muslim raiders at the Battle of Poitiers in the Autumn of 732 (or 733 according to Roger Collins). Odo's forces formed the left wing of the Frankish forces, and dealt a decisive blow when they broke into the Umayyad main camp and set it on fire. Aquitaine and its attendant marches were then formally united to Francia, but Odo, almost in his 80s and enjoying widespread popularity in his realm, kept ruling the Duchy of Vasconia and Aquitaine about the same as before until his death (probably 735).

| View of the western Pyrenees in the vicinity of the Larrau pass bridging Soule and Roncal, peak Annie in the background, from Escaliers (Harsüdürra) Credit: Iñaki LLM |

It´s not far-fetched to think that in the run-up to the Berber withdrawal during 739-742, when Berber troops gave up their positions towards the south to join the North African and Iberian Berber rebellion, the south-western fringes of Basque populated territories (present-day north of Castile, Rioja, Álava, western Navarre) were in Andalusian hands. Then a campaign led by Alfonso I is recorded, who attacked and devastated a large territory between the Ebro and the Duero (possibly Iruña-Veleia too, on the banks of river Zadorra). In the wake of the power vacuum, it's not risky to assume that the Basques retrieved part of the land formerly watched by the Berber troops, e.g. Alavese Mountains, Alavese Valleys, hilly areas of La Rioja, Oca Mountains and fringes of Bureba.

On the other hand, the debate remains wide open as to the governance of coastal areas, since whatever is the conclusion, it is made ex silentio, i.e. sources are mute. A duke of Cantabria Peter is attested as father of Asturian king Alfonso I, who may have kept a swathe of hilly areas of former Cantabria, populated by Basques, out of Andalusian reach. The marriage to Pelagius' daughter may have expanded Asturian rule to the east (as of 739), possibly up to Encartaciones.

With regards to present-day Gipuzkoa and northern Navarre, they may have remained loosely tied to the Duchy of Vasconia (see extent and organization of the Duchy of Vasconia), governed semi-autonomously by its own people, but this can only be guessed at. Later territorial and ecclesiastic organization may clarify the bonds and allegiances established by this region, when the Sancta Trinitas hermitage and cave (known today as San Adrian, located at the foot of mountain Aizkorri on an important medieval route before descending to Álava) is cited as delimiting the south-western boundary of the Bayonne diocese (Oria valley) in the late 10th century. The linguistic lead (Basque dialectal distribution) may support this assumption too in that central dialects lay to the east, while the western dialects lie to the west (imaginary line drawn by the massifs of Aizkorri, Samiño-Izaspe, Izarraitz, Arno, coastline).

In 757, Fruela succeeded Alfonso I as king of Asturias, and his forces subdued the resisting western Basques in the upper Ebro, Álava and Biscay. The Asturian king brought back from Álava a Basque maid as prisoner, Munia, to become his wife. In 755 the last governor of Al-Andalus, Yusuf al Fihri, detoured an expedition to Saragossa to quash Basque unrest near Pamplona, resulting in the defeat of the Arab army.

THE CAROLINGIANS AGAINST AQUITAINE

Circa 735, Odo died, leaving his realm to his son Hunald, who desiring the former independence challenged Charles's overlordship. Charles in turn marched over Bordeaux in 735, captured the city and in his way plundered much of northern Aquitaine, churches and monasteries inclusive. He came back in 736, this time to face the resistance of the Aquitanian counts led by Hunald, who engaged him in battle, while the exact location is not known. The outcome of the battle seems to have been beneficial for Hunald, who got a deal whereby Aquitaine's autonomy was respected in exchange for formal suzerainty to Charles. Charles did not remain in Aquitaine for long, and the Frankish leader headed south-east via the Rhone Valley to settle matters in Burgundy (i.e. impose his own followers in key positions) and fight in Septimania and Provence. Hunald abdicated circa 744 to his son Waifer, and may have retired to a monastic life on the Isle of Ré.

|

| The Carolingian Pepin III, crowned king in 752, went on to invade Septimania and unleash a terrible war against the Aquitanians and the Basques (760-768) that spurred Aquitaine's and Vasconia's feudalization |

After bringing to heel Septimania (759), the Frankish Pepin the Short unleashed a devastating war on Aquitaine as south as the Garonne on its final stage that was to have dire consequences on its population, towns and society. Waifer and his Basque troops confronted the Frankish king several times across Aquitaine, but were defeated thrice in 760, 762, and the Basques were badly defeated in 766-67, after which the Basque lords saw no option but come over to Agen and pledge loyalty to Pepin. Waifer in turn, battered by the defeats, was eventually murdered by one of his followers at the instigation (paid, according to some sources) of Pepin.

However, his son Hunald (II) rose up against the Franks, this time led by king Charlemagne after Pepin´s 768 death. Hunald II opted to flee and take refuge south of the Garonne, but at this point we know of a duke of Vasconia, Lupus II, other than the Aquitanian one. Despite providing initially shelter to his ally and rebel Hunald, Lupus backed down on his support and handed him over to Charlemagne out of fear of his military might (Charlemagne actually crossed the Garonne south). The Basque lords submitted in 769 to the Carolingian king (Fronsac < Franciacus, near Bordeaux). The Basque-Aquitanian sovereignty was over.

FURTHER READING

_________________________________________________________________________________1. Collins, Roger. 1990. The Basques. Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17565-2.

2. Meadows, Ian. 1993. The Arabs in Occitania. Saudi Aramco.

3. Euskomedia Fundazioa. Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia

2. Meadows, Ian. 1993. The Arabs in Occitania. Saudi Aramco.

3. Euskomedia Fundazioa. Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia

4. Lewis, Archibald R. 1965. Expansion into Gascony and Catalonia. The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718-1050. University of Texas Press.

- Vasconia: Early Merovingian Period (602-660)

Prehistoric megalithic monuments like this, mainly dolmens and cromlechs, were important landmarks erected at crossroads and mountain passes. Still in the Early Medieval Ages, representatives of neighbouring tribes and valleys honoured their ancestors...

- Siege Of Narbonne (752-759)

The Siege of Narbonne took place between 752 and 759 led by the Frankish king Pepin the Short against the Muslim stronghold defended by an Umayyad garrison and its Gothic and Gallo-Roman inhabitants. The siege remained as a key battlefield in the context...

- The Duchy Of Vasconia: Extent And Organization

The Duchy of Vasconia (or Wasconia) was initially (AD 602) a polity created by the Franks aimed at holding sway over the Basques. The first dukes appointed were of Germanic stock, but Vasconia was far away from the Frankish heartland and despite its suzerainty...

- Newport?s Medieval Ship Could Have Been Basque

The origins of the Newport Medieval Ship may have finally been solved ? with new research announced yesterday pointing to the north of Spain. Thanks to recent advances in tree-ring dating, experts have obtained the first scientific evidence that...

- Catching Up On Some Posts

The following (or in this case I suppose are preceding) are catch up posts: LAST CALL FOR PAPERS The End of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toulouse, the Rise of the Franks, and the 'Beginning of France': A Symposium on the Occasion of the 1500th Anniversary...

.